Silent Echoes

Notre Dame + Centre Pompidou

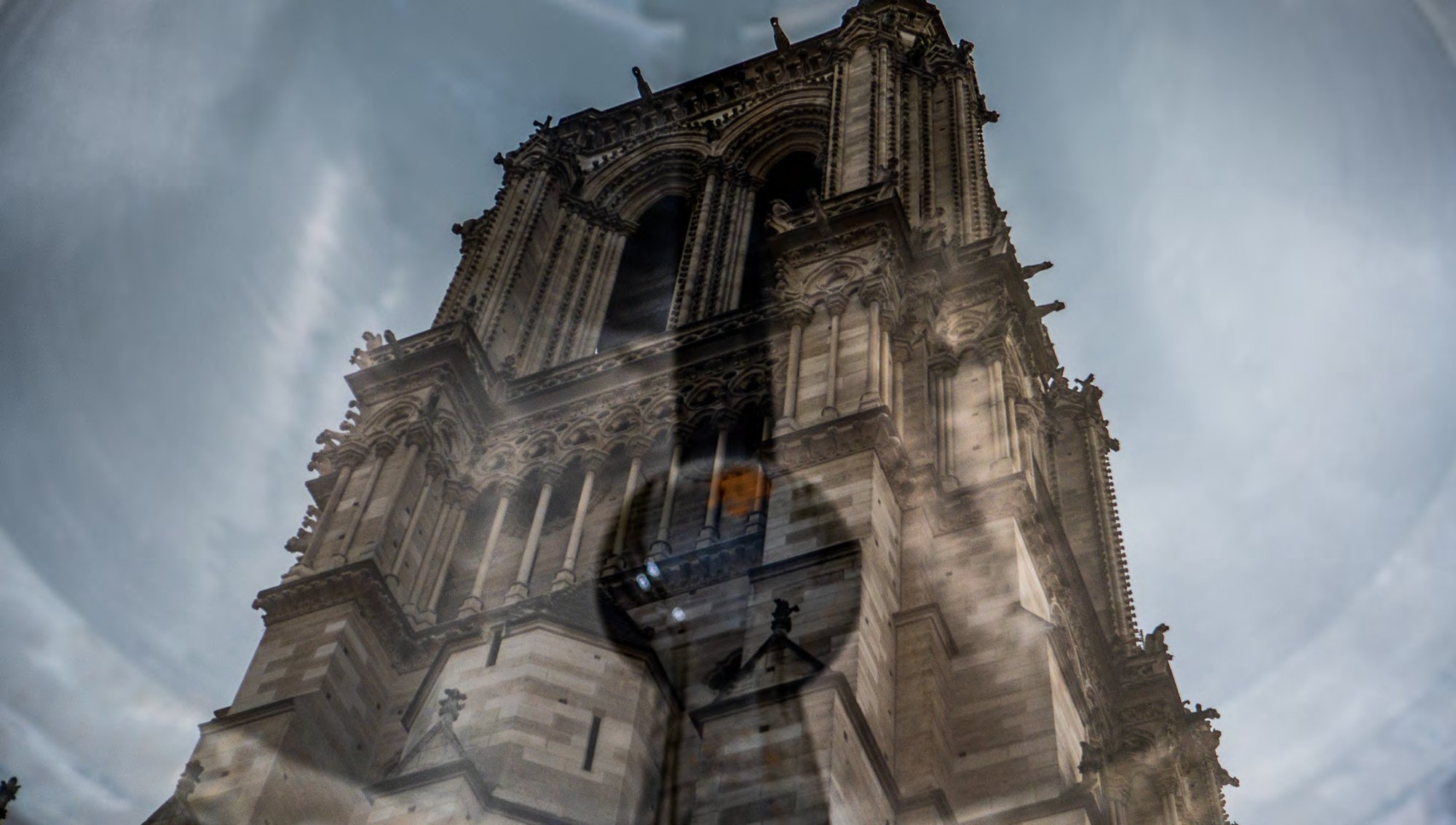

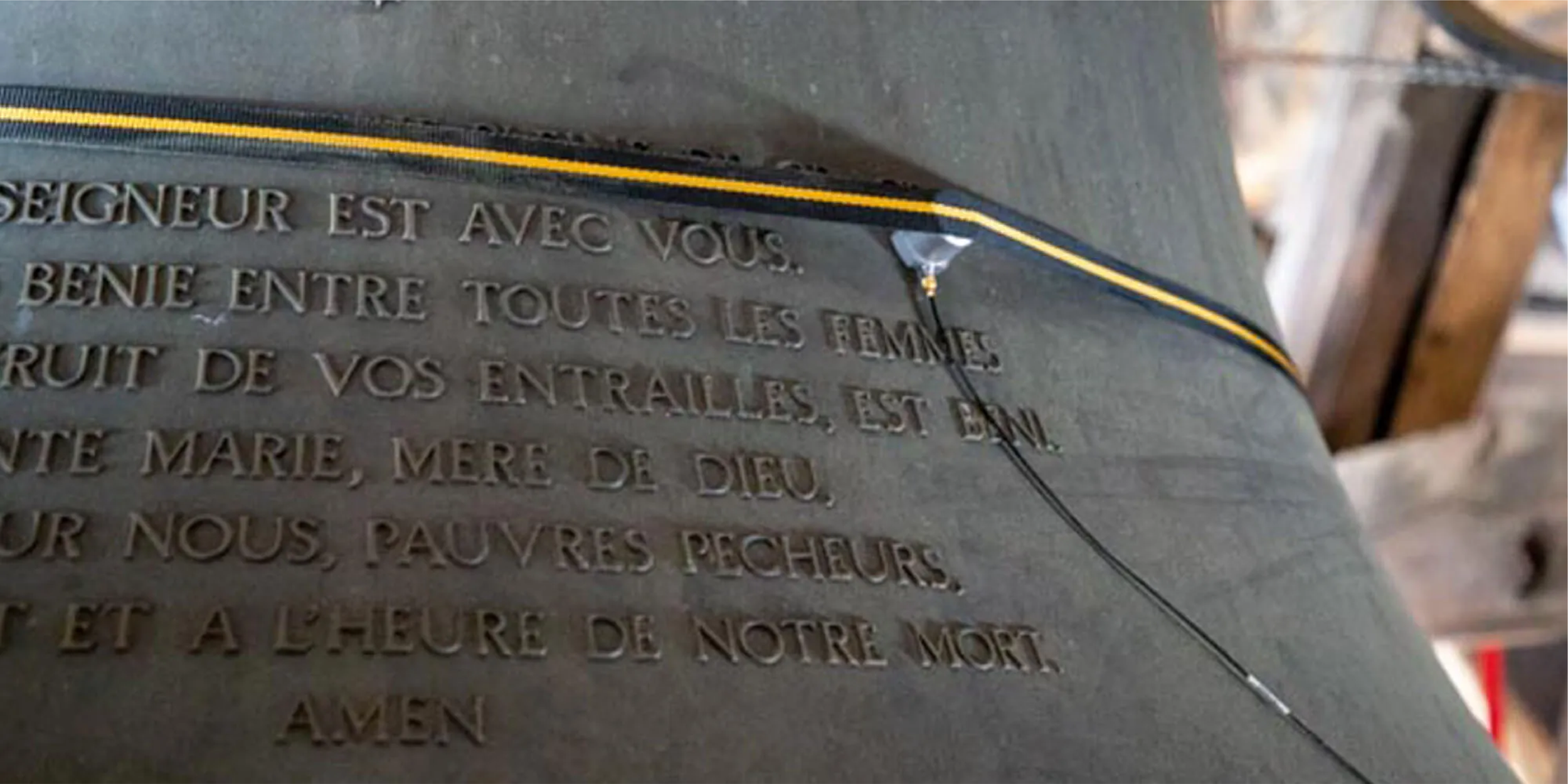

The North Tower of Notre Dame with ghost image of Emmanuel, the 17th-century bell © Bill Fontana. Inside the belfry © Friends of Notre Dame. The bell Maria with seismic accelerometer @ Bill Fontana. The terrace of Centre Pompidou with Silent Echoes installation © Centre Pompidou. Bill Fontana at the Centre Pompidou.

In this episode, we're privileged to be joined by Davia Nelson of The Kitchen Sisters, the groundbreaking, Peabody Award-winning podcast that chronicles untold stories of culture and tradition through artful and immersive audio stories.

Sound sculpture: By placing listening devices on the surfaces of built and natural monuments—the Golden Gate Bridge, temple bells in Kyoto, trees in Sequoia National Forest—artist Bill Fontana captures uncanny natural music that reveals that these bodies are alive with sound. Fontana’s latest project amplifies the voice of Notre Dame. Since the devastating fire of 2019, the ringing of the bells has ceased. To create his new work, Silent Echoes, Fontana attached seismic accelerometers—sensors designed to detect vibrations—to each of the ten bells of Notre Dame. As the bells reverberate in response to the ambient sounds of Paris—rain, the calls of birds, the noise of the street—the live feed is transmitted to a series of speakers at the Centre Pompidou creating a haunting, immersive sound sculpture. Silent Echoes debuted at the Centre Pompidou in June, where, on the fifth floor terrace of the museum, visitors stood awash in the acoustics of the bells, with the towers of Notre Dame in view just across the Seine.

In the second half of our interview, Davia Nelson of The Kitchen Sisters meets with Fontana in Paris before the opening of the exhibition. We begin our interview with my conversation with Fontana in San Francisco, just before he headed to France.

BF: I was introduced about a year ago to the woman whose title was, she was the Director General of this restoration, the official restoration entity that's in charge of the rebuilding of Notre Dame. And she agreed last July to meet me, and she invited me to come to Paris. And I met her, and on that same day, she granted me access to the Notre Dame worksite, and I had my tour of the bell towers. I made my first test recording of a bell, which was Emmanuel.

When I had my first opportunity to access the bell towers, and made my first accelerometer recording of Emmanuel, I realized that I was probably hearing a sound that nobody had heard before. Because I think I was probably, undoubtedly, the first person in the history of that bell to mount an accelerometer on it and record the sound of it not ringing.

An accelerometer is a piece of technology that is normally used by structural engineers to measure internal vibrations and machines and all kinds of structures. They're not normally used as kind of musical listening devices, but they're related to what rock musicians use as guitar pickups. They're piezoelectric transducers.

It was just like, that feeling I had the first time I put an accelerometer on Emmanuel and recorded it—it was kind of amazing. I mean, and I kept thinking like, you know that famous ancient Chinese verse, “Am I a butterfly dreaming that I'm a man or a man dreaming that I'm a butterfly?” And I kind of felt that way at that moment when I was listening to Emmanuel. And that recording that I made actually helped me a lot because it gave me some kind of physical evidence of the idea.

AC: I wondered if you wouldn't mind painting a picture of what it was like when you went up in the rafters? I'm assuming someone guided you up to…

BF: Well to enter the Notre Dame worksite, you have to be allowed to enter the Notre Dame worksite; you're required to take a lead contamination training class. Because the fire caused the roof of the cathedral to collapse, and the framing of that roof was lead. And so there's a lot of lead dust that covered everything and so you're required to take this training class, and then you go into a locker room, you have to strip down and put on protective clothing.

AC: What does it feel like to be up there?

BF: Well, you're really aware of, of course, this tremendous sense of the history of that building. And you know, when you go on the terraces of the bell towers there are these incredible gargoyles. And I feel like I've gone into a time machine of sorts, and I feel like I'm accessing some sort of hidden force in that building. Because the bells are very alive. At the end of February this year, I had a team together and I had this Danish engineering company Roland Kerr provide ten high resolution seismic accelerometers with the electronics. And we went and installed them on all ten of Notre Dame’s bells, and I made my first ten channel recordings of all the bells.

AC: Can you describe the environment in the belfry?

BF: Well, there are two ways of getting into the bell towers. The long way is you walk around the exterior of the Notre Dame, and you climb up a long spiral staircase to reach the levels of the bells. The quicker way to do it is you enter the interior of the worksite, which is full of scaffolding. And you take an elevator in the scaffolding that takes you up to a higher point, and then you get out and you're climbing on this long spiral staircase.

AC: You've obviously done work at the Eiffel Tower and the Golden Gate Bridge, how was that height and that landscape different, feel different, from those other kind of elevated places?

BF: Well with the Eiffel Tower and the Golden Gate Bridge, you don't have this feeling that time stopped. At Notre Dame, you're very much aware of this sense of time stopping. And that's why it's so interesting to do this because of the idea that these bells are actually ringing all the time, and nobody can hear it.

Next to the Centre Pompidou in the second arrondissement of Paris, Davia Nelson of The Kitchen Sisters spoke with Fontana at IRCAM, one of the world's largest public research centers dedicated to musical expression and scientific research, and a co-producer of Silent Echoes. There, they discussed the history of Notre Dame’s bells, and the breadth of Fontana's sonic work.

BF: I'm sitting in Studio One at IRCAM in Paris, and I'm just in the process of completing the installation of Silent Echoes Notre Dame at the Centre Pompidou.

DN: Have you been drawn to bells in the past? When do bells start to appear in your work?

BF: I was interested in bells as listening devices, and I think that really began very strongly when I lived in Japan in the mid-1980s, and was interested in Zen Buddhist meditation. A monk would strike the temple bell, and if you really listened with all your being to that sound, you would have the sensation that the bell never stopped ringing. When I went to Kyoto, I made some recordings of Buddhist temple bells with vibration sensors on them and revealed the fact that they're ringing all the time.

DN: They were saying that Emmanuel is the only one that survived from the beginning. What else do you know?

BF: During the French Revolution, the cathedral was stormed and a lot of the smaller bells were taken down. And some of them got replaced in the 19th century and early 20th century. But the one with the most history is Emmanuel. It's the one that's been there the whole time. Emmanuel was too big to move.

DN: Too big to fail. So Emmanuel survived. And the other ones?

BF: They were eventually all recast about twenty years ago.

DN: There's something as I'm listening to—I spent a lot of time on rivers, and there's something about the quality of that sound and that on-goingness, the eternal quality, of it. Past present future all at one time.

BF: I had the experience recently of doing a sound piece that I made in Sequoia National Park with these beautiful 3,000-year-old trees—and putting the same listening devices on the trees as I was putting on Notre Dame’s bells. And I got a beautiful sound of basically what the trees reacted to: the vibrations of the river that goes through Sequoia National Park and the flowing of the river, the vibrations of that, as they pass through the ground. And the trees can hear that vibration and they hear the rhythm of a foreign river in their own resonance. I really was fascinated by the idea that these trees were among the oldest living things on the planet. And I wanted to find out what they had to say.

DN: I feel like the Sequoias have to meet Emmanuel, and they are somewhere...

BF: Thinking about the experience, and when people go into that, they’re going to enter this incredible acoustic dream world. And the sounds are going to just surround you and envelop you. I think one thing is if somebody really engages with the sound, if they realize when they're engaged with it that what they're hearing is happening live—that it's part of the same moment—I think that'll be kind of like a very emotional realization. And there's this sense of interconnectedness, and to me that is like something kind of mystical.

A bell is normally used to mark the passage of time, birth and death, and celebrations and tragedies, all those things. But the idea that it's also receiving and the fact that nobody could hear that. And in the case of Notre Dame especially, it seemed very important to me that people could hear it.

In his narrative on Silent Echoes, Fontana includes a stanza by Rilke:

“No longer for ears…..sound

which like a deeper ear,

hears us, who only seem

to be hearing. Reversal of spaces.

Projection of innermost worlds

into the Open…..”

To learn more about the sound sculpture of Bill Fontana, visit www.resoundings.org

Sound Design by Jim McKee with editing by Emma Jackson.

Our very special thanks to Davia Nelson of The Kitchen Sisters.

I'm Alisa Carroll. Thank you for listening.

Alisa Carroll

Producer and Host

Jim McKee

Sound Design and Mixing

Emma Jackson

Editing

Band of Skulls

Theme Music