Drawing Down the Moon

Hammer Museum

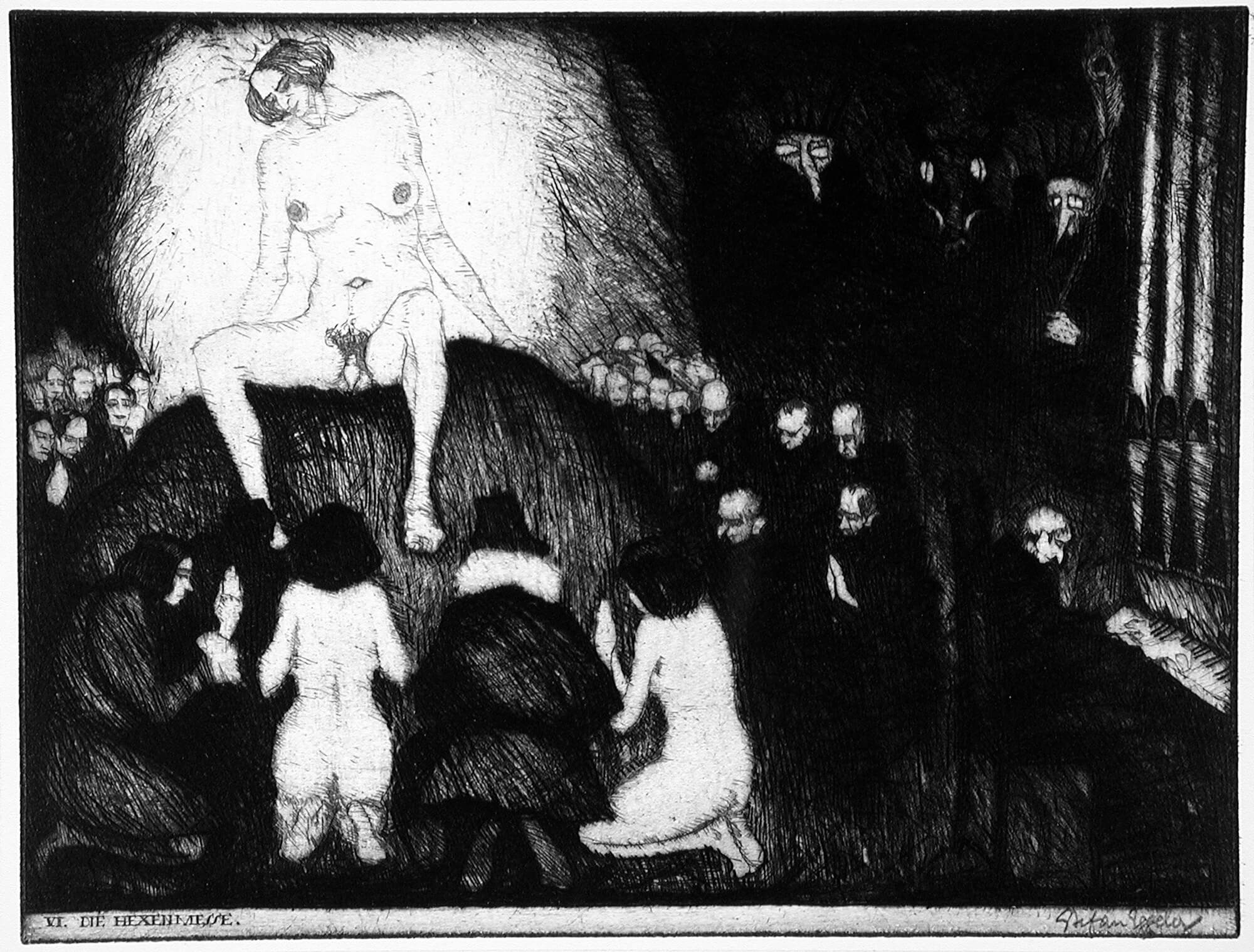

Caspar David Friedrich, A Walk at Dusk (ca. 1830-35) © The J. Paul Getty Museum; Stefan Eggeler, The Witches' Mass (1921) © LACMA; Hieronymous Wierix, Madonna and Child on a Crescent Moon (16th c.) © Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts, Hammer Museum; Lee Bontecou, Fifth Stone (Black) (1954); © Museum of Fine Arts Boston

The moon has always opened up infinite fields of perception, and in a new exhibition, Drawing Down the Moon, curator and scholar Allegra Pesenti enters those many realms, gathering lunar imagery from across centuries and civilizations that expresses the ritual, mythical, and material dimensions of the moon.

Currently Curator at Large at the UCLA Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts, she holds a PhD from the Courtauld Institute, where her focus was art of the Italian renaissance. Her exhibitions include Apparitions: Frottages and Rubbings from 1860 to Now; Zarina: Paper Like Skin, and the landmark Stones to Stains: The Drawings of Victor Hugo.

Clearly Pesenti is a master of material history. But it is also her poetic gift for the invoking the immaterial in both her writing and curation that makes her work so haunting. In her essay for the catalogue of Stones to Stains, the exhibition on the celestial drawings of Victor Hugo, she writes “the forms deliquesce and subside into an atmospheric and indefinable sense of mystery.”

What Victor Hugo wrote of his own work can also be said of the moon, that “beauty is no other than infinity contained within a contour.” We spoke with Allegra about the exhibition and her curatorial practice at the Hammer Museum in June.

AP: Drawing Down the Moon, the actual title of the exhibition I took from the book by Margot Adler, who was, apart from being an NPR journalist and reporter, a modern day Wiccan and a historian of witchcraft in America. And she chose Drawing Down the Moon as the title of her book on the history of witchcraft in America. And it relates to the act of bringing the moon down into, and expressing itself through, the body of a high priestess. And the origins of that ritual are found in ancient Greece—the Thessalian women are known to have carried out magical spells, of which Drawing Down the Moon was one of them. Ovid speaks of Drawing Down the Moon in relation to Medea, for instance. And there's a wicked connotation to it, of course, because it assumes that these women are taking over the power of the moon and activating it in earthly realms.

And I felt that Drawing Down the Moon evoked the exhibition well because it does begin in the realm of magic and in the sort of field of myth and the intangible quality of the moon, the poetry of the moon, and it works its way through to the much more concrete, tangible, material moon. Of course it also has the term “drawing” in it, which selfishly connects to my own field of expertise, which is the study of works on paper. So, in a way, it was a title that summed it all up.

A: Drawing Down the Moon surveys work from antiquity to the Renaissance to contemporary work, and while there are truly extraordinary, iconic pieces like Friedrich’s A Walk at Dusk or Bettye Saar’s Nine Mojo Secrets, I wondered if we might talk about two intriguing pieces by a much lesser-known artist, Stefan Eggeler. Would you share how you discovered those works?

AP: I can't take that claim to have discovered them. I invited an artist called Francesca Gabbiani— She's a Los Angeles based artist who's also in the exhibition—but I had invited her number of years ago to curate a Houseguest exhibition. Houseguest was a series of exhibitions that I started in, at the Hammer, oh, gosh, over 10 years ago, that consist in inviting an artist to curate an exhibition from our collections. Francesca did a fascinating survey of witches and witchcraft in hers. And I sort of I have to attribute the first gallery in the Moon show to Francesca because much of the inspiration for it came from her own Houseguest show in fact, those two Eggeler works were in her show. And he's a, you know, an eccentric German artist exploring a fascinating theme of witchcraft and the spells and the anointments. And he does it on a very small, delicate surface, but the works couldn't be more poignant in a way. There's a lot of intimacy to those works.

A: There's also a very powerful piece by the Flemish artist, Hieronymous Wierix, Madonna and Child on a Crescent Moon, the symbolism of which is “Virgin of the Apocalypse Crescent Moon.” Could you introduce us to that concept, and to this work and its imagery?

AP: Yes, the Virgin of the Apocalypse is among the most iconic scenes in Christian iconography. It's based on the vision of Saint John, in his book of Revelation, in which he records a vision he had of the Virgin rising to the skies over a crescent moon, a crescent moon placed beneath her feet. And that became the source for many images, from the medieval age all the way through to the renaissance and baroque times.

The work that you mentioned, Hieronymous Wierix, is 16th century. And it's an incredibly intricate etching of the Virgin over the crescent moon, but Wierix has reinterpreted the classical iconography of her standing over the moon, and placed her very comfortably seated over a large cushion, nestled in, enveloped, so to speak, in the upturned crescent moon. And she's backed by a radius of lines that sort of emanates from her body. So it's a very striking image, although of course, it's an etching, it's in black and white, it has a lot of tone to it. There's a lot of variation in the gradations of blacks and whites in it. So it's a particularly striking image of a very well-known iconography.

AC: And you just introduced us in the tour to the extraordinary sculptural piece that, which I felt was so moving, because as you pointed out, there's a woman's face…

AP: That's another interpretation of the Virgin of the Apocalypse. And that was new to me, too, that that particular iconography, which I've since found out was not uncommon in the Middle Ages, of placing a face within the sort of heart of the upturned moon. In this case, a female face that sort of personifies the moon, and the Virgin has her feet topped above her. So she's sort of, it's almost like a protective personification that leads the way and supports the Virgin.

AC: Somehow I find that moving because it's almost as if that were—not a pre-Christian or a Pagan—you know what I'm searching for—something that feels very elementally feminine supporting Mary.

AP: I think I think you're absolutely right. It sort of crosses into Paganism. Christian iconography often draws from ancient iconography. So there's an often an interesting, you know, crossing of influences there. And absolutely you can read that into it.

Interlude:::

AC: You have said that often one exhibition leads to the next for you. And I wondered if your study of Victor Hugo and his starlit excursions, of course, and his work at the Paris Observatory that you wrote about in Stones to Stains was a prompt?

AP: Well, interestingly, I had started working on the Moon show before I started working on Victor Hugo. This is an exhibition that has been postponed various times, even pre-pandemic, for different reasons—space, collaborations that ended up changing—so I've had the Moon show in my mind for the past six or seven years. And when I started working on Victor Hugo, it's just felt like a natural inclination to lean towards his starlit walks and to his planetary drawings, because I had the moon very much on my mind. And I was working on these two shows in parallel.

The interesting thing about Victor Hugo is that he writes this ode to the moon, and he writes it many years after his first vision of the moon through a telescope. And I think that seeing the moon through a telescope—the surface of the moon through a telescope—for the first time was so remarkably shocking to him, the fact that the telescope brought the moon so close to him, and that he was accustomed to seeing the moon as an untouchable element in the sky, a magical element in the sky, but that suddenly science made it possible to bring it down to reality; that material moon suddenly became shockingly real.

And it took him, I think, over 20, 30 years to come to terms with that shock and write about it. And when he does write about it, he writes about the dual aspect of the moon—the fact that there is this myth, there are these stories, folklores, wonderful, dreamy poems that take us to the intangible side of the moon. And yet, there's also the science, the evolving science around him, the telescopes of Paris, the scientists that are around him that are making the moon more real than it had ever been. And so he says, ‘Well, my moon sits somewhere in between those,’ because of course he had a very scientific mind, he was aware of all the scientific developments that were happening in the world, not only in France, but in America and the United Kingdom, and elsewhere. But he was also a dreamer and a poet himself. So his moon met at the crux of those two extremes. And that became a characteristic, sort of underlying characteristic of my moon show, the fact that there's that tension between the real moon and the fictional moon, and I wanted both of those sides to be represented.

“Les poêtes ont créé une lune métaphorique et les savants une lune algébrique. La lune réelle est entre les deux. C'est cette lune là que j’avais sous les yeux.”

“Poets have invented a metaphorical moon, scientists an algebraic moon. The real moon is halfway between the two. That is the moon my eyes beheld.”

Victor Hugo, Promontorium Somnii, Promontory of Dream.

AC: I feel like as a curator, that's always been a tension in your practice as well. In that I feel you have this incredibly rigorous side to your work, clearly. Your scholarship, your historical research, but then, uniquely, you have this very deeply poetic way of going about your work and your writing. Have you always felt both of those inclinations?

AP: Well, I'd never thought about it that way before. But I think doing a PhD takes you to the depths of research, you know, you're constantly asked to footnote everything to prove everything. And on the one hand, that was an extremely rigorous training for me, that I couldn't lose my mind anywhere, because I had to always come back to the proof.

AC: Your background was in renaissance work…

AP: My background was in Italian renaissance, draftsmanship to be very specific, but more generally in Italian renaissance art. And I worked at the Getty Museum in the drawings department. So I was working in the first part of my career very much on 15th, 16th, 17th-century drawings all the way up to 1900—that's sort of where the go do drawings department collection ends. But then when I when I finished my PhD, which was on the use of drawings and the communication between artists and patrons in Italy during the 16th century, I was quite adamant that was time to move on and into the present, and to remain in the field of drawings, but to start conversing with living artists about their works on paper, and their practice of making works on paper.

And that allowed me to take back maybe the less tangible qualities of curating, you know, and to maybe allow myself to be a bit more of an artist myself. And so being at the Hammer allowed me to make exhibitions that I probably wouldn't have been able to do anywhere else because I sort of stretched the boundaries. I stayed within the field of works on paper, but I went from past to present and from culture to culture. The first exhibition I did here was called Gouge: The Modern Woodcut. And it really crossed boundaries of time and culture in a way that I felt the museum allowed me to do but wouldn't have been easy to do in many other places.

AC: So Allegra, you’ve traced what we could call the immaterial in several of your exhibitions, from Apparitions to Rachel Whiteread—her drawings—to Stones to Stains, exploring the spectral and the otherworldly. And I wondered if you could share a bit about what maybe draws you to those to those feelings or those ideas?

AP: Well, that's interesting. I hadn't ever thought of it that way. But now that you're pointing towards those characteristics of my shows, I agree that they do tend to come up. I think there's a fascination with what art can do. And, for instance, in my rubbings and frottage exhibition, there was definitely an appeal to a type of drawing that captured ghostliness, how does one fix something that is not fixable? And I think that was fair to say about Rachel Whiteread too—how does one turn the emptiness of a room into a concrete form? And that is true of in a way, the Moon show, you know, how does one express something that is unreachable and untouchable in a material way?

I think it's always a challenge for the curator to find reason, find ways to do things that might seem appealing but impossible. And to find ways to actually bring those aspects to life. And it's not really the curator, it's the artists who make it possible. As a curator, I'm just finding those artists who do it and bringing them together in the room to have those conversations, but it's about finding those voices that try to make the impossible possible and try to make the invisible visible.

AC: So I found this wonderful quote, “There was a belief common to many cultures, that working rituals at the time of different phases of the moon, can bring about physical or psychological change or transformation.” And I was just thinking about this as you've been immersed in this moon study for many years now, is there one aspect that you particularly interiorized or that’s been transformative about focusing on the subject?

AP: Well, it's interesting we're speaking about this exhibition sort of at the tail end of a huge world- changing, life-changing pandemic. And serendipitously I think this is a perfect moment to be exhibiting this survey, because we've been forced into being so focused on our own bodies in the past couple of years, three years. And we've been sort of compelled, or we've been sort of unwillingly forced, to think insularly, independently, in isolation. And I think the moon is a wonderful subject now to take us out of our bodies and to think upwards and onwards and to bring us beyond our own worlds into superior realms. I think we're ready for that now. And I think it's a wonderful thing to be able to have an exhibition that in a way acts as a platform to take us into those upper realms and out of our own bodies and into a more magical place.

Drawing Down the Moon is on view at the Hammer Museum through September 11. To learn more visit hammer.ucla.edu. You can see images and read the transcript on our website, thealcoveproject.com.

Alcove’s sound design is by Jim McKee, with editing by Emma Jackson. Onsite recording for this episode by Evan Jacoby.

I’m Alisa Carroll, thank you for listening.

This episode has been edited for concision and clarity.

Alisa Carroll

Producer and Host

Jim McKee

Sound Design and Mixing

Emma Jackson

Editing

Band of Skulls

Theme Music

Music from the Episode

Puce Mary, "The Alphabet"